Below is an old short story that, until recently I’d forgotten I ever wrote. I didn’t think it was good enough now - but reading now, I’m quite proud of my younger self.

If you enjoyed my haikus about Subdistrict Rugby Union you might enjoy this. x

On Mondays, when he had a 9am lecture, Matt would see students in the red and blue blazer of his former high school. Most of them, actually all of them except the year sevens still knew who he was. Now on Tuesday, he instinctively positioned himself in such a way on the platform so that the students — heading to the south end of the station because that’s where the stairs were at Waitara — had every opportunity to nod at him as they passed. But Matt’s lecture was at 11am today, the students would be at school, probably eating recess.

Ten years of private school had not been that easy to deprogram. Matt still felt a prefect’s eye whenever he was eating chips or drinking a soft drink in public. And he still grabbed for a non-existent shoulder bag every time the doors of a Tangara closed behind him.

It didn’t help that his university residence was the same bedroom he’d spent his entire childhood. Or that he travelled there from the same train station, just down the north shore line to Redfern instead of up to Hornsby.

Matt looked down at his dirty, white Havaianas thongs, perpendicular to the train tracks each with a tiny Australian flag near the toe. He thought about his mates who’d pissed off to do vocational degrees in regional centres: Commercial Radio Production at Charles Sturt in Bathurst, Sports Psychology at UC in Canberra. He thought about their text messages and phone calls. Of residence halls full of young people plodding around in tracksuits. Of $1 shots at Mooseheads and hooking up in O-week with a girl who cooked two weeks worth of bolognese at a time.

He thought about how, in spite of being told that everything would be better, nothing had happened yet. There was just less stuff to do since school. Matt had joined the social skiing club which everyone said was basically the social drinking club and they’d given him a bottle opener for his $5, but what happened after that? He would see their flyer about a party and would attend it — and everyone is friends ‘cos they all have a bottle opener keyring?

Matt had walked around at O-Week, past stalls of people playing with yo-yos and writing poems and laughing theatrically with clipboards and he’d smirked at them and found them embarrassing.

But, unlike high school, where not being found embarrassing by Matt held value, the University of Sydney campus was almost solely powered by embarrassing people. Embarrassing people thrived at university. They wrote for Honi Soit, they dressed as clowns and juggled in the quadrangle, they drank coffee in the Wentworth building in diverse groups of people that didn’t all go to the same high school.

Matt couldn’t bring himself to being embarrassing, or even just embarrassed. So instead, he’d been forced to retreat to the few, less than ideal people he already knew that shared similar timetables. This was usually Dave Lam, who was friends with all the old Grammar guys who wore suede slip on loafers and hung out with the girls from one of those other eastern suburbs schools who wore Bettina Liano jeans and flat-heeled boots — also suede — that sagged around the ankle, gave off a pirate silhouette. But even saying that Matt was retreating was overstating it, because apart from Dave Lam, none of that gang spoke to him. When he thought about it, he didn’t really know any of the girls’ names apart from one or two of them and only because they were famously hot. And he was pretty sure they didn’t secretly know his name.

The sun was bright over Gordon Station and Matt squinted toward the stairs. A figure approached him, which he recognised as a smiling Rocky Boosalis. Rocky had gone to the same school as Matt but had finished seven or eight years earlier, putting Rocky in his mid-20s. Matt knew him from Old Boys Rugby Club, they played second grade together.

Rocky had recently gone back to uni — he was studying to be a teacher. He looked like a photocopied illustration of an ancient Greek in the PHIL 1001 reader (he was Greek). Tall, bulging calves.

Matt cleared his throat: “How’s it going, Rocky?”

Rocky smiled, nodded at the space behind Matt. “Just in time.”

Matt looked over his shoulder to see the train — the pre-Tangara model Matt preferred out of nostalgia — coming approaching from around the bend. “Ah sweet.”

Rocky was cool, but only because he was in his 20s. He wore casual clothes very neatly: his green t-shirt was ironed and his denim shorts finished just above the knee, ankle sports socks and cross trainers, backpack clipped around the chest with that little strap, rubber water bottle in a front pocket designed specifically for a rubber water bottle. Even though Rocky had gone to the same school as Matt, it was not during the time Matt had attended, so Matt could count him as a non-school friend which felt important today.

The train doors hissed, lurched open and Matt and Rocky climbed on. Rocky lead the way upstairs, flipping a seat so they could sit across each other on two two-seaters.

“What’s on today, Matty?”

“Sociology. Lecture then the tute at three. Yourself?”

“Education prac. Not until three. Though. Got the dentist first.”

“Fair enough.” Matt said. “Training tomorrow night?”

“Indeed.” Rocky lightly drummed his thighs with his palms. “Did you, ah, celebrate in full force with the others last week?”

The previous week, their club had had their least unsuccessful round of the year against Old Ignatians. Third and first grades both got flogged, but fourths had won and seconds drew. The pub had put two kegs on — it was only meant to be one per win, but they were the first non-losses of the season. The place went nuts.

Matt and the few other 18-year-olds huddled together at these things, observed with horror and awe and wild approval at the men in their 20s and 30s drinking themselves empty. Mittens, the club president — he’d finished high school the year Matt was born — staggered around the space like a red kangaroo, shouting the bar and dropping his heavy arm around the shoulders of his clubmen. At one point, when one of the fourth graders went out to go to the toilet, Mittens pulled his dick through the fly of his jeans and flopped it into the absent fourth grader’s almost-full beer. Mittens held both his arms out to the side, fully exposing himself while his grey penis hung in the amber liquid. He grinned maniacally at Matt and his teenaged mates in the corner: ‘Yes, young blokes! Future clubmen of the fucken year.’

“Yeah, it was crazy!” Matt said. “They made Ben Baker scull a beer that Mittens’ put his dick in.”

Rocky nodded. “Yeah, Mittens does that sort of thing sometimes.”

“Where were you?” Matt said. “Free drinks.”

“Nah.” Said Rocky. “Had a dinner with some friends.”

“Oh, right.” Matt said.

Rocky unzipped his bag and rested an education faculty reader on his lap.

“Have you played many seasons?” Matt said. “For Old Boys?”

“A few, yeah.” Rocky said. “Played first two seasons out of school. So ‘96 and ‘97. Then I went travelling for a year. Then I had a year where I was here but didn’t play. So that makes this my sixth? Wow.”

“Yeah, right.”

“So, I’ve seen plenty of those big nights out.”

“Did you do something else at uni? When you first left school?”

“Yeah, I started studying commerce at New South. But it didn’t work for me that time round.”

“Yeah, right.”

Matt wasn’t used to talking to adults.

“How are you enjoying uni life?”

“Dunno.” Matt said. “It’s only twelve hours a week. Have essays due soon — haven’t started.”

Rocky smiled, looked down at his blue, EDUC 1064 reader. There were handwritten notes in the margins of the page he was on. Not only had he done his readings, he’d written notes and was revising them once more.

The train stopped and Matt looked up. He hadn’t noticed they were in the Ws already — Wollstonecraft and Waverton — The two tiny stations between St Leonards and North Sydney that hardly anyone ever got on or off at.

Rocky noticed too. He folded the white page on his reader at the corner, closed it shut and put it back into the backpack sitting between his feet. He freed his plastic squeeze bottle from its holster in the front, took a gulp and returned it.

“Oh yeah, before I forget.” Rocky said. He reached into his backpack, pulled out a business card and a pen, wrote something on it and handed it back to Matt.

Matt looked down at the card. It was for St Matthew’s Anglican Church in Wahroonga. Matt drove past it whenever he went to Hornsby.

Matt looked up and Rocky smiled back at him kindly, broadly and with no sarcasm or irony. “If you’re ever interested, or if you’d just like someone to talk to. Even just a chat.”

“Okay. Cheers, Rocky.” Matt said.

The train pulled into North Sydney station and Rocky stood up, pulled on his backpack and clipped the the strap across his chest. “This is me. Have a good one, Matty.”

“Seeya tomorrow.”

Rocky got off the train and loped up the platform. A few more people, mostly in suits, joined the train. Matt looked at the card. He hadn’t known that Rocky was religious, but now he thought about it, the way he dressed and how he didn’t go to the pub sort of made sense. Also, if he gets on the train at Gordon he probably still lives with his parents. These felt like the kind of things a 25-year-old christian might do.

The card featured an outline illustration of the old church’s building and basic details in a simple font. On the back Rocky had written “Rocky” and his phone number in blue biro.

It was a kind gesture by Rocky. Matt already suspected that he would probably never be the kind of man that dries beer of his dick with a tea towel. And now, in the same way, or a slightly different one maybe, he also knew that he’d never have any use for Rocky’s card. Or Rocky’s church group. Or Rocky’s mobile number.

The train stopped at Milson’s Point then continued towards the city. Matt looked out the window as the train pushed onto the harbour bridge, more or less keeping pace with the southbound taxis and buses. It was almost jumper weather but the sky was bright which made the harbour shine navy blue.

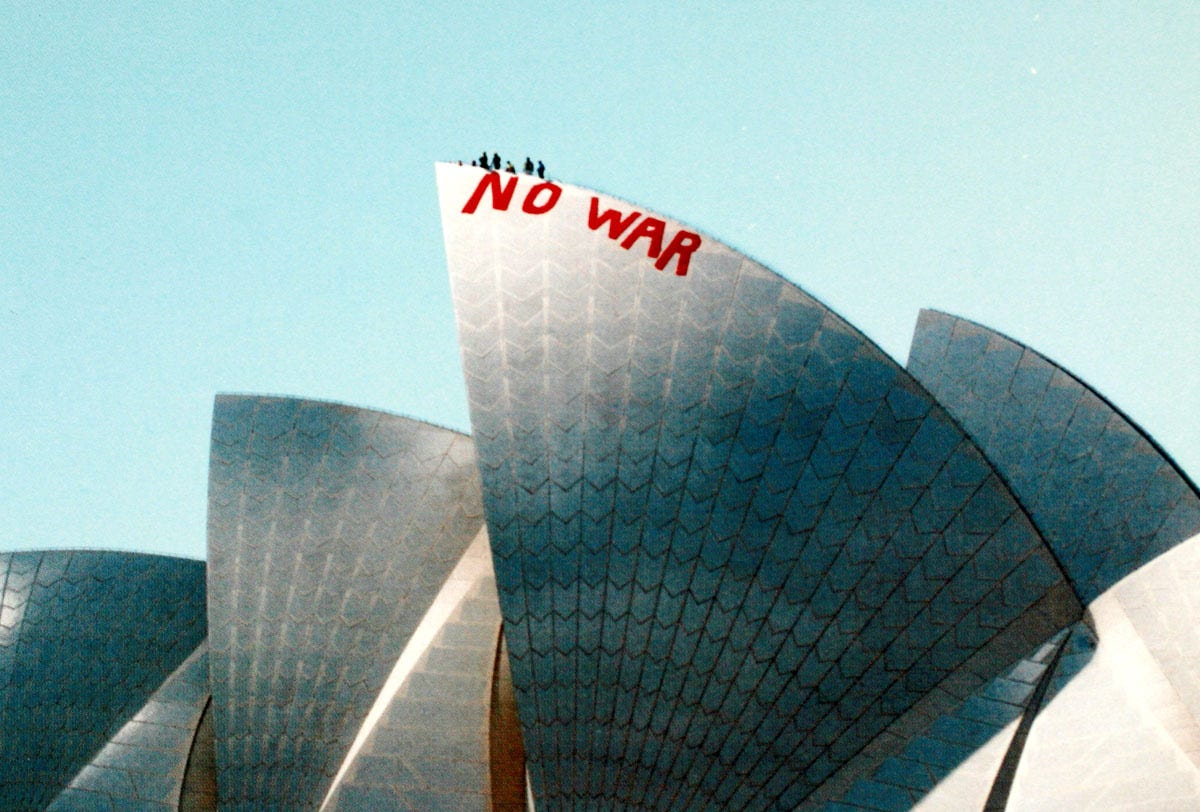

The train passed the Sydney Opera House which, today, Matt noticed, had the words “NO WAR” scrawled in red paint across the top left of its front sail. More accurately, it was the remnants of the words as the process of scrubbing it off was already underway care of abseiling workers in high-vis.

Later that day, Matt would pick up a newspaper and read about British astronomer Dr Will Saunders, 42 and Australian environmental activist, Daniel Burgess, 33 and feel with utter undergraduate conviction that their answer was as good anyone else’s.

But this morning, he just stared out the window. The red words came and went from his vision as the train continued south, over the last of the Harbour Bridge, past Circular Quay, past the Cahill Expressway and on toward the sociology lecture that would be cancelled due to illness.